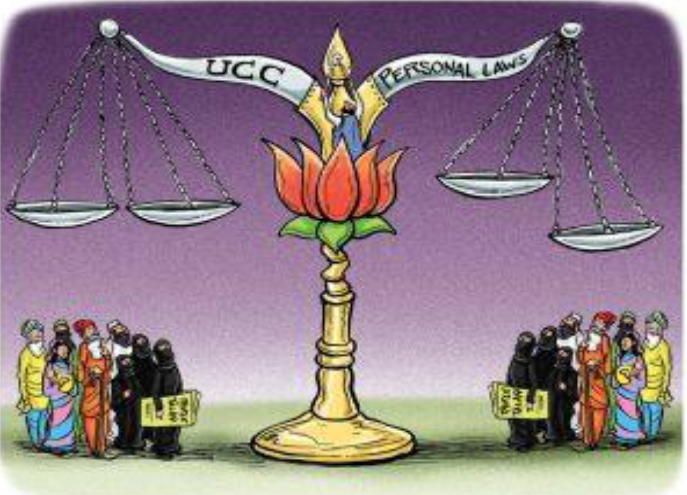

India is a diverse, pluralistic country and home to people of different faiths. The Constitution of India recognizes the right to one’s religion and right to preserve one’s culture as some of the fundamental rights of Indian citizens. India’s plurality and diversity have manifested itself in its laws as well. Marriages and divorce in India, as well as other practises such as inheritance, are governed either by personal religious laws or by secular laws.

Personal religious laws may be defined as the body of laws which apply to a person solely on the ground of that person belonging to a particular religion. Secular laws are basically legislations enacted by the Parliament on marriage and divorce which are not specific to any religion and can be made applicable to a citizen irrespective of her/his religion.

Personal religious laws apply to persons by default and may be codified or uncodified. Most of Hindu Personal Laws are codified, and the law governing marriages and divorces for Hindus is The Hindu Marriage Act 1955.

Secular legislations do not apply by default and to be governed by secular law, persons have to opt for it at the time of their marriage by registering their marriage under the equivalent secular law. For example, Hindus can opt out of the personal law of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 by registering their marriage under the secular law of The Special Marriages Act 1954. Secular laws are of course of particular importance for couples who choose to marry when the individuals belong to different faiths.

Remember that personal laws apply based on a person’s religion and secular laws apply based on a citizen’s choice to opt out of personal laws.

The Legislative History of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955:

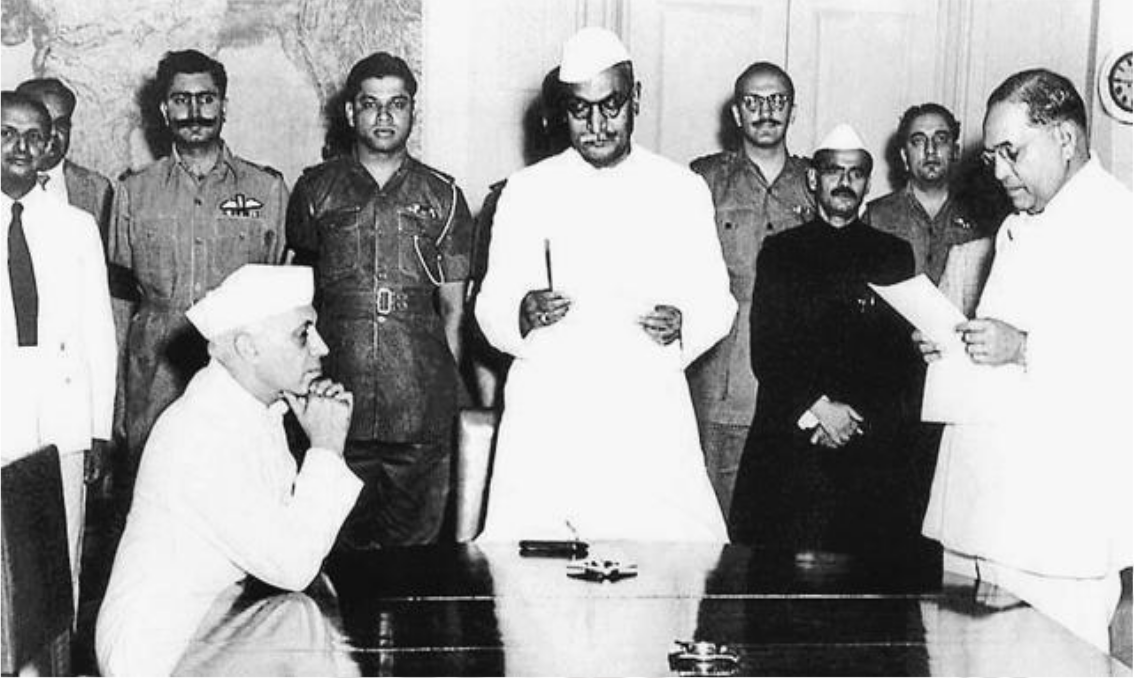

Dr B. R. Ambedkar, who had a dominant role in drafting the Indian Constitution, became the first Law Minister of India with Jawaharlal Nehru as the first Prime Minister of India. Under the Nehru led government, a committee was formed with Dr B. R. Ambedkar as its chairperson and was tasked with the responsibility to codify Hindu personal laws. This committee formulated and drafted legislative bills which were called “The Hindu Code Bill” that aimed at codifying Hindu personal laws governing matters of marriage, divorce, adoption, maintenance and custody.

The Hindu Code Bill received great opposition from the then President of India, Dr Rajendra Prasad and several congressmen. Many people saw The Hindu Code Bill as an intrusion into their religion. Some radical Hindus thought the Hindu Code Bill would drastically reform Hindu Personal Laws. While some Hindu Dalits did not consider themselves as Hindus. Due the impending elections, the Nehru Government decided to defer their agenda for The Hindu Code Bill. Due to such opposition and deferment, Dr B. R. Ambedkar resigned in protest in 1951, and The Hindu Code Bill lapsed due to re-elections.

In 1952, the then Law Minister C. C. Biswas moved the Parliament for passing of The Hindu Code Bill. The members of the Parliament realized that it was an impossible task to pass and enact The Hindu Code Bill as a whole and thus segregated it into three bills: (1) The Hindu Marriage and Divorce Bill, (2) The Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Bill, (3) The Hindu Succession Bill.

The Hindu Code Bill was finally enacted in 1955 – 1956. The Hindu Marriage Act 1955, that earlier formed part of The Hindu Code Bill, was enacted to amend and codify marriage and divorce laws between Hindus, thus hoping to make them consistent across the country.

Applicability and Overriding effect of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955:

As mentioned earlier The Hindu Marriage Act 1955, being a codification of Hindu personal law, was made applicable and is applicable, not to all citizens of India but only to Hindu citizens. The applicability of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 is wider than it appears as it also applies to all Indic religions including Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists. Section 2 of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 explicitly makes The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 applicable to Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists.

Though there were objections raised in Parliament against such wide applicability of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955, the law when passed continued to carry Section 2. Till date, many authors and citizens from the communities of Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists criticise Section 2 of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 for its applicability to minority religions and see this law as an intrusion into the religious affairs of minority religions.

It is important to note that The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 is also applicable to a person who has converted or re-converted to be a Hindu, Buddhist, Jain or Sikh. The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 is also applicable to legitimate and illegitimate children, where either both or one of the parents are Hindus, Buddhists, Jains or Sikhs by religion, or one of whose parents is a Hindu, Buddhist Jain or Sikh by religion and who is brought up as a member of tribe, community, group or family to which such parents belongs or belonged.

By virtue of Section 4 of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955, this codified piece of Hindu personal law overrides any un-codified Hindu personal laws that run contrary to its codified provisions. The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 forms the sole source of Hindu personal law on marriages and divorces.

Marriage under The Hindu Marriage Act 1955: Conditions of a valid marriage, void and voidable marriages, registration of marriages

CONDITIONS OF A VALID MARRIAGE

Section 5 of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 specifies the conditions that must be met for a valid Hindu marriage.

A marriage between two Hindus is considered as valid if the following conditions are met:

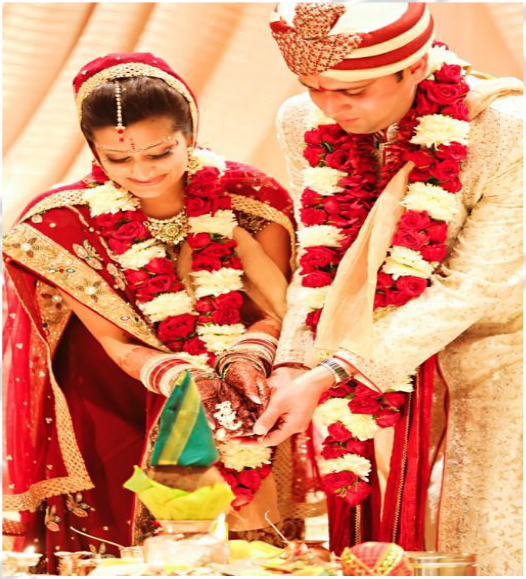

Section 7 of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 states that a Hindu marriage is solemnized when undertaken in accordance with the customary rites and ceremonies of either party thereto. The majority of the Hindu marriages require seven steps by the couple jointly around a sacred fire (the saptapadi) for the marriage to be solemnized.

Under Section 18 of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 failure to meet certain conditions to marriage prescribed under Section 5 of The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 may lead to punishment in the form of simple imprisonment which may extend to one month, or with fine which may extend to one thousand rupees, or with both.

If conditions mentioned under Section 5 are not met, the marriage is either void or voidable under Sections 11, 12 and 17 of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955. A void marriage is a marriage that has no legal status from the commencement, and a voidable marriage is a marriage that has a legal status until the time the court of law passes a decree of annulment.

If conditions (1), (4) and (5) as listed above are not met, then the marriage will be void. If condition (2) is not met the marriage will be voidable. Further, if the bride is pregnant with a child of another man or the marriage is not consummated due to impotency, then the marriage is voidable.

REGISTRATION OF MARRIAGES

Section 8 The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 provides for registration of marriages but such registration is not mandatory, and failure to register does not make the marriage invalid.

Registration of marriage leads to an entry of the particulars of the marriage in the Hindu Marriage Register maintained by State authorities. This registration serves as evidence of marriage. Some State Legislatures have amended Section 8 The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 and made rules for registration.

The Supreme Court of India and the High Courts have recommended that registration of marriages shall be made compulsory.

Divorce under The Hindu Marriage Act 1955: Who can divorce; when and where can they file for divorce; grounds for divorce; and remarriage

WHO CAN DIVORCE, AND WHEN AND WHERE CAN THEY FILE FOR DIVORCE

The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 entitles both the husband and the wife to file a petition before the courts of law for divorce. A divorce petition can only be filed in a court of law after one year since the date of the marriage has elapsed. The reason behind this is that marriages in Hinduism are considered to sacred, and it is believed that the couple should attempt to make the marriage work. In exceptional circumstances, courts of law may admit a petition before the completion of one year of marriage.

A petition for divorce shall be presented to the District Court within the local limits of whose ordinary original civil jurisdiction:

Further, Section 23 of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 mandates the courts of law to, before granting any relief under this Act, endeavour to bring about a reconciliation between the parties and refer the matter for reconciliation to be undertaken within a reasonable stipulated time period. However, this duty of the courts of law is not applicable if relief is sought on any of the grounds specified in Section 13(1) clause (ii-vii). These grounds include: conversion into another religion, unsound mind, husband missing for 7 years, incurable disease, and renouncement of the world.

GROUNDS FOR DIVORCE

A Hindu may petition for divorce on the following grounds as prescribed under Section 13 clauses (1), (1A) and (2) of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955:

Further, a wife may seek a divorce also under Section 13 (2) on the grounds that:

Pursuant to Section 13-B of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955, both husband and wife together can claim divorce on grounds of mutual consent.

The Supreme Court in 2006 case recommended to the Union of India to amend The Hindu Marriage Act 1955 to incorporate another ground for divorce in the following words:

“Before we part with this case, on the consideration of the totality of facts, this Court would like to recommend the Union of India to seriously consider bringing an amendment to the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 to incorporate irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a ground for the grant of divorce. A copy of this judgment is sent to the Secretary, Ministry of Law & Justice, Department of Legal Affairs, Government of India for taking appropriate steps.”

The Law Commission of India has explained “irretrievable breakdown of marriage” as follows: “a ground which the Court can examine and if the Court, on the facts of the case, comes to the conclusion that the marriage cannot be repaired/saved, divorce can be granted. The grant of divorce is not dependent on the volition of the parties but on the Court coming to a conclusion, on the facts pleaded, that the marriage has irretrievably broken down.”

Irretrievable breakdown of marriage is a recognized ground for divorce in countries like New Zealand and England.

Despite there being no law on irretrievable breakdown of marriage, in another 2006 case, the Supreme Court of India while granting a divorce ruled as follows:

“We are fully convinced that the marriage between the parties has irretrievably broken down because of incompatibility of temperament. In fact, there has been the total disappearance of emotional substratum in the marriage. The matrimonial bond between the parties beyond repair and that the marriage has been wrecked beyond the hope of salvage and therefore public interest and interest of all concerned lies in the of the recognition of the fact and to declare defunct de jure what is already defunct de facto.”

Even as far back as in 1996, the Supreme Court of India in the absence of a law on irretrievable breakdown of marriage, ruled that: “…the marriage between the appellant and the respondent has irretrievably broken down and that there was no possibility of reconciliation, we in the exercise of our powers under Art. 142 of the Constitution of India hereby direct that the marriage between the appellant and the respondent shall stand dissolved by a decree of divorce.”

In 2013, A Marriage Laws (Amendment) Bill was introduced and passed in the Rajya Sabha to amend the Hindu Marriage Act 1955 and incorporate irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a ground for seeking a divorce. This Bill was not taken up by the Lok Sabha and thus did not become law.

A Hindu who has been divorced can marry again once the divorce has been finalized, that is once the period of filing an appeal against the divorce has expired or the appeal having been filed has been dismissed.

Judicial Separation:

The courts of law can using their discretion, treat a petition for divorce as one for judicial separation. Judicial Separation means that a couple is living separately pursuant to a court order being passed but are still married. Such a court order can be procured by the husband/wife by filing a petition praying for a decree for judicial separation on any of the grounds specified in Section 13(1) and (2).

Appeal and Enforcement of Court decrees relating to marriage, divorce or judicial separation:

Under Section 28 of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955, court decrees granting or refusing divorce are appealable by both husband and wife, whoever is unsatisfied with the court decree within 30 days from the date of the court decree. It is important to note that a court decree is not automatically enforceable. Pursuant to Section 28A of The Hindu Marriage Act 1955, all court decrees and orders in marriage or divorce proceedings, shall be enforced in the like manner as the court decrees and orders made in the exercise of its original civil jurisdiction for the time being enforced.

Conclusion:

So as the position stands today, Hindu Personal Laws are in codified form. There exists enacted legislations on matters of Hindu marriage, divorce, adoption, succession, and maintenance. The advantage of having Hindu Personal Laws codified is that chances of misuse of Hindu Personal Laws are relatively lower as the codified legislations are explicit and clear in language. Also, divorce is a court driven process, prevents divorce being given on grounds other than those that are reasonable.

| you can view video on Marriage and Divorce under Hindu law |  |

Reference

Rights of Women and Children Copyright © by Meher Dev. All Rights Reserved.